Is Earth Becoming Too Hot for Humans? Climate Change Facts & Risks

Oct, 19 2025

Oct, 19 2025

Wet-Bulb Temperature Calculator

This calculator shows the wet-bulb temperature based on air temperature and relative humidity. When wet-bulb temperatures exceed 35°C, outdoor exposure becomes lethal.

Key thresholds:

- ≤ 30°C: Comfortable

- 30-35°C: Increasing risk of heat exhaustion

- ≥ 35°C: Lethal within hours of exposure

Wet-Bulb Temperature

Last summer, a city in the Middle East recorded a wet‑bulb temperature that pushed the human body past its survivable limit. That headline isn’t a futuristic sci‑fi plot; it’s a glimpse of what could become routine if the planet keeps heating up. Below we break down the science, the numbers, and what the trends mean for everyday life.

What Global warming is and why it matters

Global warming is a long‑term rise in Earth’s average surface temperature, driven primarily by greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane. The phenomenon intensifies the natural greenhouse effect, trapping more heat in the atmosphere. Scientists track it using a global network of surface stations, satellites, and ocean buoys.

Since the pre‑industrial era (around 1850), the average temperature has climbed about 1.2°C. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns that each tenth of a degree past 1.5°C dramatically raises the risk of irreversible damage.

How we measure the heat that threatens Human habitability

Habitability isn’t just about average temperature. It’s about how heat stresses the body. Scientists use three key metrics:

- Wet‑bulb temperature - combines heat and humidity; values above 35 °C are lethal after a few hours of exposure.

- Heat index - perceived temperature that accounts for humidity; high values increase dehydration risk.

- Heat stress - physiological strain measured by core body temperature and heart rate.

When any of these cross critical thresholds, outdoor work, even short walks, become dangerous.

Temperature thresholds and what they mean for people

| Temperature rise (°C) | Key climate impacts | Human habitability risk |

|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | Reduced Arctic sea‑ice, coral bleaching, increased extreme heat events | Wet‑bulb temperatures exceed 35 °C in limited regions; adaptable with mitigation |

| 2.0 | More frequent droughts, sea‑level rise ~0.3 m by 2100, widespread heatwaves | Wet‑bulb 35 °C reached in large parts of South Asia, Middle East, and US Southwest |

| 3.0 | Massive ice sheet loss, >1 m sea‑level rise, collapse of many ecosystems | Heat stress becomes chronic in subtropics; outdoor labor unsafe for billions |

These numbers aren’t abstract. Cities like Phoenix already see summer wet‑bulb readings above 30 °C, and models predict they’ll breach 35 °C under a 2 °C scenario.

Real‑world examples of heat pushing limits

In 2023, Delhi recorded a heat‑stress index of 58 °C, causing hospitals to overflow with heat‑related illnesses. In 2024, a town in Kazakhstan experienced a wet‑bulb temperature of 35.5 °C for three consecutive days, forcing schools to close.

These events illustrate a pattern: once the atmosphere holds enough moisture, the heat becomes lethal even at temperatures that previously felt merely uncomfortable.

What the science says about future habitability

Climate models from the NASA Earth‑Observing System show that without aggressive emissions cuts, the probability of crossing the 35 °C wet‑bulb threshold in densely populated regions exceeds 60% by 2050.

Conversely, pathways that limit warming to 1.5 °C keep those extreme wet‑bulb events under 10% probability in the same timeframe, according to the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C.

Key takeaways:

- Every 0.5 °C matters. The jump from 1.5 °C to 2 °C triples the area where wet‑bulb >35 °C.

- Regional differences are stark. Coastal high‑latitude zones may stay tolerable longer, while inland subtropics face rapid decline.

- Adaptation helps but has limits. Air‑conditioning can reduce indoor heat stress but spikes electricity demand, potentially worsening emissions if the grid isn’t clean.

How societies can reduce the risk

Mitigation and adaptation go hand‑in‑hand. Here are proven strategies:

- Decarbonize energy: Shift from coal to wind, solar, and nuclear to cut carbon emissions faster than 2030.

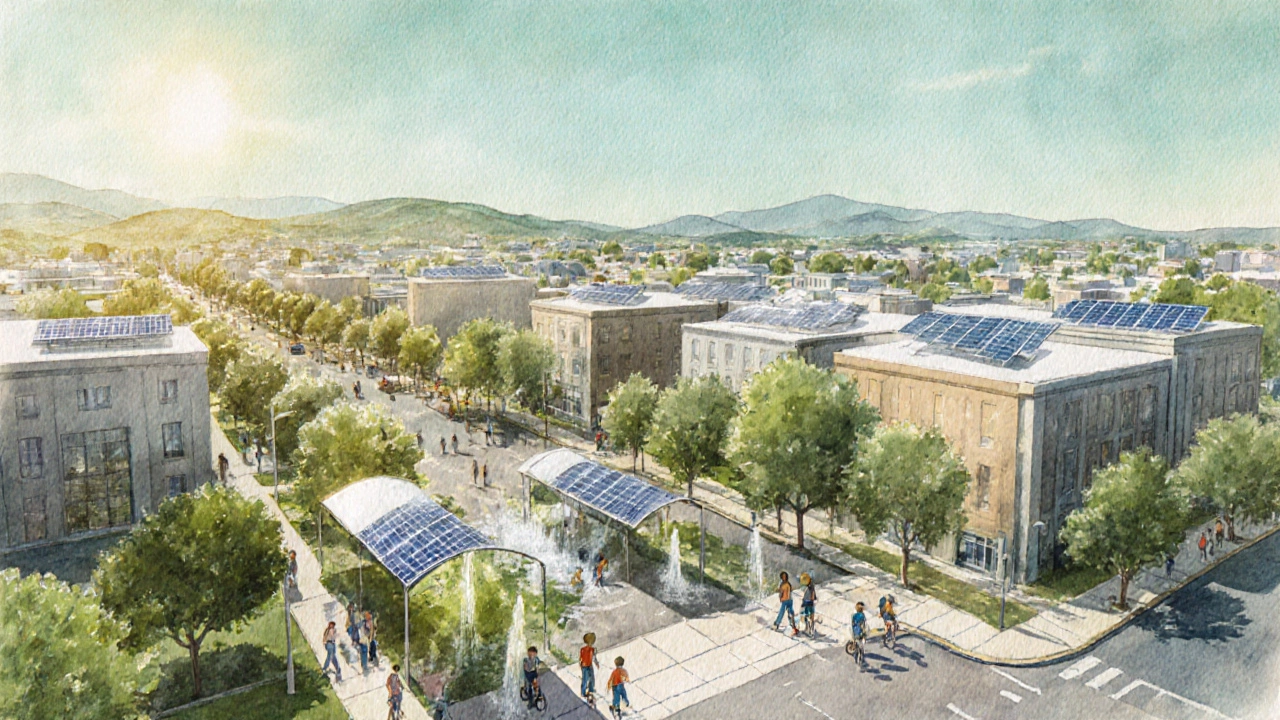

- Urban redesign: Increase green spaces, reflective roofing, and cool pavements to lower ambient temperatures.

- Heat‑early‑warning systems: Provide real‑time wet‑bulb alerts so workers can adjust schedules.

- Building standards: Enforce ventilation and insulation standards that keep indoor temperatures safe without excessive cooling.

These actions not only curb temperature rise but also improve air quality and public health.

Common misconceptions

Many argue that humans have survived past warm periods, so we’ll be fine. While early humans endured higher average temperatures, they lived in pre‑industrial ecosystems with lower baseline humidity and without modern infrastructure that concentrates people in heat‑intensive cities.

Another myth is that technology alone will solve the problem. Air‑conditioning can only buy temporary relief and consumes huge amounts of energy-often from fossil fuels-creating a feedback loop.

What you can do today

Individual actions add up:

- Reduce personal carbon footprint: use public transport, eat less meat, and improve home insulation.

- Support policies that fund renewable energy and climate‑resilient infrastructure.

- Stay informed about local heat alerts and adjust outdoor activities accordingly.

Every degree we keep off the planet buys more time for adaptation and protects the health of billions.

Will Earth become uninhabitable for humans?

If global warming exceeds 2 °C, large swaths of the planet will regularly exceed the wet‑bulb temperature limit for human survival. That doesn’t mean total extinction, but it would make outdoor life impossible in many regions and strain food and water systems.

How reliable are wet‑bulb temperature forecasts?

Modern climate models, validated against decades of observational data, predict wet‑bulb trends with high confidence at regional scales. Local forecasts improve further with high‑resolution weather models.

Can air‑conditioning keep us safe?

Air‑conditioning reduces indoor heat stress, but it spikes electricity demand and can increase emissions if the power grid isn’t decarbonized. It’s a short‑term fix, not a long‑term solution.

What temperature rise triggers the most severe risks?

Crossing the 2 °C threshold markedly expands regions where wet‑bulb temperatures exceed 35 °C, pushing many densely populated areas into chronic heat stress zones.

How do renewable energy sources help with heat risk?

Renewables replace fossil fuels, cutting CO₂ emissions that drive warming. Cleaner grids also lower air‑conditioning’s carbon footprint, creating a double benefit.